|

- 积分

- 13286

- 威望

- 13286

- 包包

- 34831

|

Nature:血液与血液的联接

* ]4 L$ J4 P W& m- u0 V5 p来源:生物360 / 作者:Dee / 2015-01-29

. W q) M5 u" V* E$ I3 f6 }& o0 \- r1 }3 y* \) k& E

- I* |. D/ C" x- p0 P8 m - I* |. D/ C" x- p0 P8 m

科学家们通过将动物联接起来,从而证明年轻动物的血液能够使年老动物的组织重新焕发活力。如今,科学家正在测试这种方法是否能够在人类身上应用。) g- ^) c0 o0 P/ _

两只小鼠肩并肩地依偎在一起,啃食着同一颗食物小球。当其中一只小鼠向左边转身时,你就可以清楚地发现:这两只小鼠所共享的东西不仅仅只有食物——它们的前腿和后腿已经被绑到了一起,躯体上有一排整齐的缝合线,将它们的皮肤紧紧地连接在了一起。然而在它们的皮肤下面,研究者以另一种更为彻底的方式将这两只小鼠连接到了一起:它们的心脏正在抽运着彼此的血液。+ ?1 j" f9 x, J; D2 |

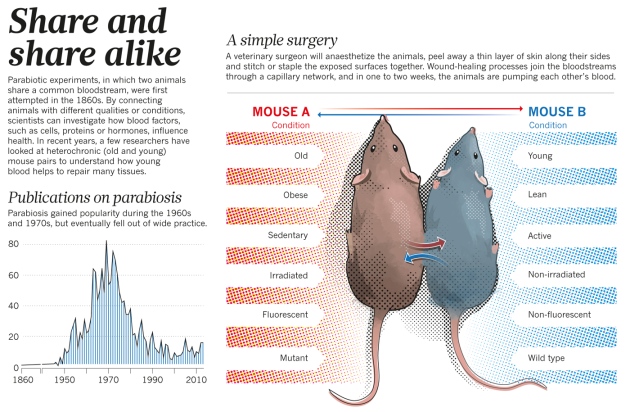

异种共生(parabiosis)是一项拥有150年历史的外科技术,它能够将两只活体动物的血管连接起来。(异种共生的英文名来源于希腊语para和bios,本意分别为“并排”和“生存”。)这项技术模拟了自然界中天然存在的共享血液供给的案例,例如连体双胞胎或者在子宫内共享胎盘的动物。. i7 }- n6 h( C- B; l

在实验室内进行的异种共生研究将为我们提供一个难得的机会来检验这样一个问题:当某只动物血液中的循环因子进入到其他动物体内时,这些因子将会发挥何种功能?异种共生啮齿动物实验已经为内分泌学、肿瘤生物学和免疫学领域带来了重大突破,但是这些实验大多数是在35年前开展的。由于一些尚不清楚的原因,这项技术自20世纪70年代之后就逐渐淡出了人们的视线。4 e# ^2 B; [, M' D/ O* r

然而在过去的几年里,少数实验室重新开展了异种共生实验,尤其将其应用于衰老领域的研究。科学家将年老小鼠的循环系统联接到年轻小鼠的循环系统上,从而获得了一些引人注目的成果。年轻小鼠的血液似乎能够为衰老器官(包括心脏、大脑、肌肉和几乎所有被检测的其他组织)带来新的活力,从而使年老小鼠变得更加强壮、聪明和健康,甚至能让它们的皮毛变得更有光泽。如今,这些实验室已经开始着手确定年轻小鼠血液中有哪些成分可以引起这些改变。去年9月份,科学家在加利福尼亚州开展了一项特殊的临床试验,将首次测试年轻人血液可以为年老的阿尔兹海默病患者带来哪些益处。1 Y$ t& @) d' @: \4 f

开展这项研究的公司是由加利福尼亚州斯坦福大学(Stanford University)的神经病学家Tony Wyss-Coray所创建的,他认为这是一种返老还童的现象。他们正在重新启动衰老的时钟。5 i* h2 w) Z& k' W3 p+ H

而Wyss-Coray的很多同事则较为谨慎地做出声明。马萨诸塞州剑桥市哈佛大学(Harvard University)的干细胞研究员Amy Wagers说:“我们并不是一种能够抵抗衰老的动物。”Wagers已经在年轻小鼠的血液中找到了一种可使肌肉重新充满活力的因子。Wagers认为,这类因子并不会将衰老组织变成年轻的组织,而是帮助衰老组织修复损伤。“我们正在恢复组织的功能。”( i3 S. `$ q* k4 a

她强调指出,目前还没有人能够令人信服地证明年轻动物的血液能够延长寿命,也无法保证这一情况是否真实存在。但是她仍然指出,年轻动物的血液或其中的因子可能能够帮助老年人在手术后恢复健康,或者有助于治疗老年病。

( v! C( z& H2 L$ s; x6 i美国国家老化研究所(National Institute on Aging,位于马里兰州贝塞斯达)神经科学实验室(Labora¬tory of Neurosciences)的主任Mark Mattson虽然并未参与异种共生的研究工作,但是他也说道:“这项工作令人非常兴奋。”他半开玩笑地说:“它促使你去思考。或许我应该储存一些我外孙的血液,如果我开始出现认知问题时,我将得到一定的帮助。”

4 C. ]) D; a' ^9 K5 Q两只共生动物的力量% F$ O. t9 [8 |# `! b

最早有记载的异种共生实验是由生理学家Paul Bert在1864年开展的。当时,他先去除了两只小白鼠体侧的一条皮肤,随后将两只小鼠缝合到一起,希望能够创造一个共享的循环系统。生物学完成了剩下的工作:随着皮肤缝合处重新长出毛细血管,自然的伤口愈合过程最终将两只小鼠的循环系统联接到了一起。Bert发现,注射到一只小鼠血管中的液体能够毫不费力地进入到另一只小鼠体内——这项研究工作使得Bert在1866年获得了法国科学院(French Academy of Sciences)的奖励。

) _# `# s2 `5 g$ P2 y自从Bert开创性地进行异种共生实验后,其实验步骤并未发生太大的改变。研究者已经在水螅(与水母有关的、淡水中的小型无脊椎动物)、青蛙和昆虫身上进行了这项实验,但是啮齿动物的实验效果最佳,这是因为啮齿动物在手术后恢复情况较好。到20世纪中叶时,科学家们便利用成对的异种共生小鼠或大鼠来研究各种各样的生物学现象。例如,某个研究团队利用一对异种共生大鼠进行试验,最终否定了以下观点:龋齿是由于血液中的糖分所导致的。他们每天仅喂给其中一只大鼠一定量的葡萄糖,由于异种共生大鼠共享循环系统,因此它们的血糖水平相当,然而仅有那只食用葡萄糖的大鼠患上了龋齿。 o0 e& B7 M6 ]; W- l8 p

纽约州伊萨卡康奈尔大学(Cornell University)的生物化学家兼老年医学家Clive McCay是首个将异种共生实验应用于衰老研究领域的科学家。1956年,他的研究团队将69对大鼠缝合到了一起。这些大鼠涵盖了几乎所有不同的年龄段,其中包括将1.5月龄的大鼠和16月龄的大鼠联接起来——相当于将5岁的人同47岁的人进行联接。这个实验的效果并不理想。McCay研究团队在研究工作说明中写道:“如果两只大鼠不能够很好地适应彼此的话,其中一只大鼠会啃食另一只大鼠的脑袋,直到嚼烂为止。”在69对共生大鼠中,有11对死于一种名为共生病(parabiotic disease)的神秘疾病;两只大鼠缝合在一起后大约一到两周内就会发生共生病,这种疾病可能是一种特殊的组织排斥反应。

1 {- u& V# O/ Q9 d9 d* Y如今,研究者都非常谨慎地开展异种共生实验,以减轻实验动物的不适程度,降低死亡率。斯坦福大学的神经病学家Thomas Rando在研究中需要使用异种共生实验,他说:“我们对实验小鼠进行了详尽的观察,并且与动物保护委员会进行了长时间的讨论。”“我们不会掉以轻心的。”相同性别的、体型相近的小鼠在被缝合到一起之前,彼此之间已经共同生活了两周,而且研究者们在无菌环境下进行异种共生手术,手术过程中还使用了麻醉法、取暖电毯和防止感染的抗生素。在异种共生实验中使用遗传背景匹配的近交系实验小鼠,似乎就能够降低共生病的发病风险。相联接的小鼠可以正常进食、饮水和活动,并且还能够成功地将它们分离开来。

( X% Q( g' g9 g2 z9 Y* T6 y! h& s; U在McCay的首例异种共生衰老实验中,年老大鼠与年轻大鼠被缝合在一起9-18个月之后,年老大鼠的骨骼在重量和密度方面与年轻大鼠的骨骼相近。在15年以后,也就是1972年时,加利福尼亚大学(University of California)的两位研究者研究了共生的年老大鼠和年轻大鼠的寿命。年老大鼠的寿命比对照组的寿命长四到五个月,从而首次表明,年轻动物的血液循环可能会影响寿命。

+ G# S" M3 G& C7 Y4 p尽管异种共生实验获得了如此有趣的研究结果,但是它竟然逐渐被人遗忘了。研究异种共生发展历程的科学家推测其中可能的原因是:当时的研究者也许认为他们已经从研究中获得了所有可被发现的结果,抑或是伦理学机构对异种共生研究的审批门槛变得非常高。无论出于何种原因,异种共生实验中断了。直到干细胞生物学家Irving Weissman的出现,异种共生研究才得以重新出现在研究者的面前。

]! X2 f( N( @& f2 `( |* K溯本追源

. t% r K. U& w+ O: E4 Z/ G1955年,在蒙大拿州大瀑布城的一个小镇医院病理学家的指导之下,16岁的Weissman学会了如何将小鼠缝合到一起。他的指导老师当时正在研究移植抗原(transplan¬tation antigen)。移植抗原是位于移植细胞或组织表面上的一大类蛋白质,它能够决定移植细胞或组织是否会被宿主接受还是排斥。Weissman还清楚地记得,当他往其中一只共生小鼠的血液内加入一种荧光示踪剂时,就观察到了荧光示踪剂在两只异种共生的动物之间来回游走。他说:“这真是太不可思议了!”2 [) g, `. s6 `2 b" w% y* p0 o

在接下来的三十年里,他继续潜心研究史氏菊海鞘(Botryllus schlosseri,一种天然存在的联体生物)的再生现象及其干细胞。1999年,当Wagers还是Weissman斯坦福大学实验室内的一名新入职的博士后研究员时,她希望能够研究造血干细胞的运动和命运,因此Weissman建议她使用异种共生的小鼠,并且在其中一只小鼠体内对她想追踪的细胞进行荧光标记。Wagers的实验很快就发现了两个关于造血干细胞特质及其迁移情况的研究结果。她的研究也激发了斯坦福大学一些同事的研究灵感。" O) ]! B) E( s9 z1 c" z" Y

2002年,Rando实验室的博士后Irina Conboy在一次文献报告会上详细介绍了Wagers的一篇论文。Irina的丈夫Michael Conboy同样也是该实验室的博士后,而他当时却在会议室后排昏昏欲睡。- n! U! V' s& U, C9 m

当Irina提到将小鼠缝合到一起时,Michael突然被惊醒了。Michael说:“这么多年以来我们一直都在讨论这样一个问题:机体内的所有细胞似乎都会发生衰老,而所有的组织似乎会同时发生衰老。”但是他们一直都没有想出一个切合实际的实验,来研究机体老化的调节机制。$ Z1 j( }) B( _5 r. ^* d* s

Michael说:“我(听到异种共生实验,)当时就想:‘嗨,等一下,这两只小鼠共享血液。这或许就能够回答我们多年以来一直都在思考的问题。’”文献报告会结束后,他冲到Irina和Rando面前。当Michael还没有阐述完他的想法时,Rando就说:“我们开始这样做吧!”% k, k- b! u7 a4 ]6 F, ~$ _' C

他们与Wagers展开合作,Wagers负责在异种共生实验中缝合年老小鼠和年轻小鼠,并且将这项技术传授给Michael(见“有福同享,有难同当”)。Rando指出,他并没有预料到这种实验能够有效地说明问题,但是它确实有效。年轻动物的血液主要通过促使衰老的干细胞重新开始分裂,从而能在五周之内让年老小鼠的肌肉和肝细胞恢复活力。2005年他们发表了一篇论文,详细描述了这些研究结果。此外,该研究团队也发现,年轻小鼠的血液可以促进年老小鼠脑细胞的生长,但是这一结果并未写入2005年的论文之中。总而言之,他们的研究结果最终表明,血液中含有一种或几种可调节不同组织衰老过程的神秘因子。" V# Z% X, k7 h

Rando团队发表了研究结果之后,他的电话就开始响个不停。其中有一些电话是由一些男性健康杂志打来的,他们正在寻找锻炼肌肉的方式;其他电话则来自于一些着迷于预防死亡的人。他们都想知道,年轻动物的血液是否真的能够延长寿命。然而,尽管在20世纪70年代时就有研究结果提示这一可能性的存在,但是目前仍然没有人能够验证这一想法,因为这是一场费财费力的实验。

* C0 p/ X3 ?1 h# _ `9 }! _' yRando研究团队的成员反而解散开来,分别研究血液中到底有哪些成分可以使人“返老还童”。 Irina和Michael Conboy在团队解散后入职于加利福尼亚大学伯克利分校。他们在2008年时发现,肌肉活力的恢复与促进细胞分裂的Notch信号通路的活化作用有关,或者与阻碍细胞分裂的转化生长因子β(transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β)通路的失活作用有关。随后在2014年时,他们在血液中确定了一种抗衰老因子:催产素(oxytocin);众所周知,催产素是一种参与分娩和促进人类情感的激素,它已经成为一种被美国食品及药物管理局(FDA)批准的、可用于孕妇引产的药物。无论是男性还是女性,催产素水平都会随着年龄的增长而降低,当我们往年老小鼠体内注射催产素时,这种激素的水平在一两个星期内就能够快速地激活肌肉干细胞,重新生成肌肉组织。1 a2 n6 d! ?1 ?; t' G( f

所有脏器的情况' h( w- U: k$ M% V1 l% ~1 j

Wagers随后在哈佛大学中继续从事抗衰老研究工作,并且在2004年时组建了自己的实验室。她招募研究不同器官系统的专家,帮助她评价年轻动物的血液对各个器官组织的影响。在英国剑桥大学(University of Cambridge)神经系统科学家Robin Franklin的帮助下,她的研究团队发现年轻动物的血液能够促进年老动物受损脊髓的修复;在哈佛大学神经系统科学家Lee Rubin的帮助下,她发现年轻动物的血液能够刺激年老动物的大脑和嗅觉系统生产新的神经元;在马萨诸塞州波士顿布莱根妇女医院(Brigham and Women’s Hospital)的心脏病学家Richard Lee的帮助下,她发现年轻动物的血液能够逆转由于年龄所导致的心壁增厚。

4 d2 V, H" N# I在Lee的帮助下,Wagers开始筛查有哪些蛋白质在年轻动物血液中含量丰富、但在年老动物血液中含量却很少。有一种蛋白质“脱颖而出”:生长分化因子11(growth differentiation factor 11, GDF11)。Wagers和Lee指出,如果直接注入GDF11的话,就足以能够增加肌肉的力量和耐力,逆转肌肉干细胞内的DNA损伤。除了Wagers实验室以外,目前还没有其他的实验室在小鼠研究中验证这一发现,但是有人在果蝇中发现了一种类似的蛋白质,能够延长寿命、预防肌肉退变。

" V/ n& H; d/ B2 o# [可以说,异种共生重新获得了研究者的关注,并且在各个密切相关的实验室内广为传播。Wyss-Coray在Rando实验室旁边的办公室内工作。他之前就已经发现,在老人和阿尔兹海默病(Alzheimer’s disease)患者的血液中,蛋白质和生长因子的水平发生了显著的变化。他根据Rando尚未发表的大脑研究结果,利用共生的年老小鼠和年轻小鼠,证明年老小鼠在接触年轻小鼠的血液后,其神经元的生长速度确实增快了,而年轻小鼠在接触年老小鼠的血液后,其神经元的生长速度则降低。而单用血浆也能够产生相同的效果。Wyss-Coray说:“我们并不需要进行全血的交换。”“它(即血浆)就像一种药物似的。”Wyss-Coray研究团队随后观察了异种共生小鼠大脑的整体变化情况,他们发现,年轻小鼠的血浆能够激活年老小鼠的大脑可塑性和记忆形成过程,增加年老小鼠的学习能力和记忆力。Wyss-Coray说:“难以置信,这居然能够发挥这种功效!”

* h3 [4 q& r9 U$ A V& {审稿者也难以相信这一研究结果。Wyss-Coray指出,当他第一次将这些研究成果投稿到某期刊时,就被无情地拒绝了,拒稿的回应是“结果好得不像是真的”。因此他的研究团队在加利福尼亚大学旧金山分校花费了一年的时间重复该实验——由不同的研究者利用不同的设备、仪器和工具进行实验。他们最终得到了同样的研究结果。Wyss-Coray说:“在那之后,我才真正放下心来。”“我确信这真的有效。”4 I6 }5 h7 V( t' P1 }/ W7 T

去年5月份,Wyss-Coray发表了他的研究工作,引起了香港一家公司的注意。掌管这家公司的家族拥有阿尔兹海默病家族史,该病的特征是神经元不断丢失。据报道,在给这个家族的成员输注血浆后,其中一个人的病情得到了暂时性地改善。因此这家公司投资了一大笔启动经费,以便将Wyss-Coray的方法转化到人体临床试验中去。Wyss-Coray在加利福尼亚州门洛帕克成立了一家名为Alkahest的创业型公司;2014年9月份,该公司在斯坦福大学启动了一项有安慰剂对照的、随机双盲的临床实验,检测年轻人血浆治疗阿尔兹海默病的安全性和有效性。该试验计划招募18名年龄均在50岁或以上的阿尔兹海默病患者,目前研究者已经开始向6名患者体内输注30岁或以下男性健康人的血浆。研究者除了监测患者的疾病症状外,还会仔细寻找脑部扫描X光片和疾病相关性血液生物标志物的变化情况。& w+ m3 Z8 S0 Y9 a: h

无效的血液?5 t/ X8 J2 F; L, N4 P1 k; s4 h

Wagers迫切渴望看到结果,但是她也担心难以解释实验失败的原因,这可能会使得整个研究领域的进展出现倒退。例如,30岁捐赠者的血浆内可能并不含有那些有利于阿尔兹海默病患者的因子。Wagers、Rando和其他研究者还是更倾向于选择那些特殊的合成性血液因子或者已知因子的组合进行实验,并检测它们的治疗效果,因为人们已经完全了解这些因子的作用机制了。8 b* ?) e! z3 y& N0 J: q% ^

年轻人血液中的干细胞通常处于活化状态,因此研究者还存在着一些挥之不去的疑虑:如果长时间地激活干细胞,是否会引起细胞分裂过多呢?Rando说:“我怀疑,使用血浆、药物等进行长期治疗,虽然能够使年老动物的细胞恢复活力,但是也会增加肿瘤的发病率。”“即便我们知道如何使细胞变年轻,我们还是希望能够审慎地开展这项工作。”3 R/ V/ i, y3 {; v3 f2 _) c2 Y

Michael Conboy则为另一个原因而担忧:他已经看到过很多异种共生小鼠死于共生病,因此在人类身上试用时就应当更加慎重了。他指出,“我会非常谨慎地”对待任何往老年人体内定期输注大量血液或血浆的临床试验。Alkahest公司的首席执行官Karoly Nikolich指出,他能够理解人们对这种疗法所产生的安全性担忧,但是他也强调指出,人类已经安全地接受了几百万次输血和输血浆了。 h9 Q! c5 N: ^) p" R; v" N# ]$ J

Alkahest公司的初期研究预计将在今年年底得出结论,而公司也计划开展一些更深入的研究,来测试年轻人的血浆是否能够治疗不同类型的痴呆和年龄相关性疾病。

' {5 }5 e7 u; M1 ^1 h由于抗衰老研究领域中的希望曾不断遭遇破灭,因此人们对年轻人血液所持有的谨慎态度都是合理的。在过去的二十年里,研究者们已经确定了多种具有抗衰老功能的治疗方法,包括限制热量的饮食、葡萄皮中的化学成分白藜芦醇(resveratrol)、可保护染色体完整性的端粒酶(telomerase)、可延长小鼠寿命的免疫抑制剂雷帕霉素(rapamycin)以及随着人类年龄增长其功能和数量会下降的干细胞。

0 X' l$ M* x* W5 q1 W' ?经证实,其中只有两种方式能够有效地延缓或逆转衰老对多种哺乳动物组织造成的影响,即热量限制和雷帕霉素,但是这两种疗法均不能用于抗衰老治疗。前者在灵长类动物的研究中可产生相互矛盾的结果,而后者则会产生毒副作用。) T' q0 t5 L: X N; q- c

而相比之下,年轻人的血液似乎能够逆转衰老造成的健康影响,并且可能不会对人体产生一些已知的安全性问题,反而目前在多个实验室内开展的异种共生衰老研究已经证实:年轻人的血液可以产生一些证据确凿的健康效应。但是科学家和论理学家仍然担心,在我们尚未完全掌握这种治疗方法的安全性和有效性证据之前,这种治疗方法会在人体上进行非法试用(当然除了已经获批的临床试验以外)。Mattson提醒道,干细胞移植法虽然未获得当局的审批,但是目前已经成为了一个蓬勃发展的产业,而未经当局批准的年轻人血液输注法可能更容易成为一种迅速发展的行业。. i( ~4 r& Q7 r9 s7 n! U4 H

明尼苏达大学(University of Minnesota,位于明尼阿波里斯市)的生物伦理学家Leigh Turner主要研究抗衰老研究领域的伦理学问题,他说:“我们通常会在尚未开展可靠的研究工作之前,便在如此薄弱的基础之上建立一些有利可图的市场。”

Q( y+ T- a8 |* D* r4 _, y l就目前而言,任何声称年轻人的血液或血浆可延长寿命的言论都是错误的:我们现有的研究数据还不足以说明这一点。如果想验证这类言论正确与否,还需要开展一项耗时六年的实验——首先要等待小鼠成长到足够的年龄,然后等着它们自然死亡,最后才能分析数据。Michael Conboy说:“如果我们有资金进行这项实验的话,我很乐意做,但是我们并没有资金。”然而他也补充道:“我希望有人正在某地开展这项实验。”

0 A" S3 }3 N/ C原文检索:( }5 U- D/ q( Q: q

Ageing research: Blood to blood

. X1 m% B* O! v; m$ ^By splicing animals together, scientists have shown that young blood rejuvenates old tissues. Now, they are testing whether it works for humans.

7 p D: {8 I: f/ g& s2 F3 p

- R. M1 M, W6 ~Megan Scudellari 21 January 2015 Article tools PDFRights & Permissions

' X7 y3 F! Y O: a( Y# F! o* i

- }' r+ w3 t/ m U7 r- DIllustration by Gary Neill

! Y' T/ L' y. iTwo mice perch side by side, nibbling a food pellet. As one turns to the left, it becomes clear that food is not all that they share — their front and back legs have been cinched together, and a neat row of sutures runs the length of their bodies, connecting their skin. Under the skin, however, the animals are joined in another, more profound way: they are pumping each other's blood.7 C- s H: l/ E

; Y f( v: P# X, z- D6 l- u* iParabiosis is a 150-year-old surgical technique that unites the vasculature of two living animals. (The word comes from the Greek para, meaning 'alongside', and bios, meaning 'life'.) It mimics natural instances of shared blood supply, such as in conjoined twins or animals that share a placenta in the womb.; p* k0 W. h5 K, b. x

! B8 x) n" r' f1 T, wIn the lab, parabiosis presents a rare opportunity to test what circulating factors in the blood of one animal do when they enter another animal. Experiments with parabiotic rodent pairs have led to breakthroughs in endocrinology, tumour biology and immunology, but most of those discoveries occurred more than 35 years ago. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the technique fell out of favour after the 1970s.

, D5 k# F% u; }5 o7 {( r& h! S6 L+ [9 [3 {8 K6 B- _; h$ w2 l0 b* `

In the past few years, however, a small number of labs have revived parabiosis, especially in the field of ageing research. By joining the circulatory system of an old mouse to that of a young mouse, scientists have produced some remarkable results. In the heart, brain, muscles and almost every other tissue examined, the blood of young mice seems to bring new life to ageing organs, making old mice stronger, smarter and healthier. It even makes their fur shinier. Now these labs have begun to identify the components of young blood that are responsible for these changes. And last September, a clinical trial in California became the first to start testing the benefits of young blood in older people with Alzheimer's disease.3 i' n7 ^' O. V! V2 Z! J* k7 [

7 z4 ~ T" K9 W+ Z6 d: n) A1 HLISTEN; g: E& A4 }5 c+ {+ O5 G

Science writer Megan Scudellari discusses the rejuvenating effects of young blood

3 S! x4 K+ }' x) c" ~00:00

, h9 o, ]$ `4 b, C“I think it is rejuvenation,” says Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurologist at Stanford University in California who founded a company that is running the trial. “We are restarting the ageing clock.”

8 D7 ~6 y6 z8 n, G0 O4 i* c" W4 y7 N; Q2 Q' }

Many of his colleagues are more cautious about making such claims. “We're not de-ageing animals,” says Amy Wagers, a stem-cell researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who has identified a muscle-rejuvenating factor in young mouse blood. Wagers argues that such factors are not turning old tissues into young ones, but are instead helping them to repair damage. “We're restoring function to tissues.”# r5 L, m) @- k+ O8 i5 |6 p

3 Q8 P" q+ p7 g! q# e+ \

She emphasizes that no one has convincingly shown that young blood lengthens lives, and there is no promise that it will. Still, she says that young blood, or factors from it, may hold promise for helping elderly people to heal after surgery, or treating diseases of ageing.

: q7 ~3 D' L/ v2 S, B) v# S, C8 \( ]. \& D; L O* j% W1 H

“It's very provocative,” says Mark Mattson, chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the US National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland, who has not been involved in the parabiosis work. “It makes you think. Maybe I should bank some blood of my daughter's son, so if I start to have any cognitive problems, I'll have some help,” he says, only half-joking.

+ Q( o2 {; Y# @" G9 R3 I$ h4 T4 J- ?+ R

The power of two

* U; a/ F4 x/ K+ g( t0 `5 iPhysiologist Paul Bert performed the earliest recorded parabiosis experiment in 1864, when he removed a strip of skin from the flanks of two albino rats, then stitched the animals together in hopes of creating a shared circulatory system1. Biology did the rest: natural wound-healing processes joined the animals' circulatory systems as capillaries regrew at the intersection. Bert found that fluid injected into a vein of one rat passed easily into the other, work that won him an award from the French Academy of Sciences in 1866.8 A' v6 p, p& f' l3 [. O/ P

" x/ P* z, a p: V# x% b8 ~

Since Bert's initial experiments, the procedure has not changed much. It has been performed on hydra — small freshwater invertebrates related to jellyfish — frogs and insects, but it works best on rodents, which recover well from the surgery. Up to the mid-twentieth century, scientists used parabiotic pairs of mice or rats to study a variety of phenomena. For example, one team ruled out the idea that dental cavities are the result of sugar in the blood by using a pair of parabiosed rats, of which only one was fed a daily diet of glucose. The rats had similar blood glucose levels owing to their shared circulation, yet only the rat that actually ate the sugar developed cavities2.

1 p. {. P K3 Y7 S& Q4 I0 o* K% {/ u p8 m# z8 ?; |& H

, g$ k* {9 P" T. T/ Y" I8 r+ VNik Spencer/Nature; Chart Data: A. Eggel & T. Wyss-Coray Swiss Med. Wkly 144, W13914 (2014)6 b7 r d6 o" |2 Y* M, a

Expand7 s/ W! L7 ^. j6 M1 z1 J

Clive McCay, a biochemist and gerontologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, was the first to apply parabiosis to the study of ageing. In 1956, his team joined 69 pairs of rats, almost all of differing ages3. The linked rats included a 1.5-month-old paired with a 16-month-old — the equivalent of pairing a 5-year-old human with a 47-year-old. It was not a pretty experiment. “If two rats are not adjusted to each other, one will chew the head of the other until it is destroyed,” the authors wrote in one description of their work4. And of the 69 pairs, 11 died from a mysterious condition termed parabiotic disease, which occurs approximately one to two weeks after partners are joined, and may be a form of tissue rejection.

( V# |" G4 j6 Q) x- `! C- B% i; X2 f

- N0 q; I+ x/ A- d( eToday, parabiosis is performed carefully to reduce animal discomfort and mortality. “We observe the mice at length and have long discussions with our animal-care committee,” says Thomas Rando, a Stanford neurologist who has used the procedure. “We don't take this lightly.” Mice of the same sex and size are socialized with each other for two weeks before attachment, and the surgery itself is done in a sterile setting with anaesthesia, heating pads and antibiotics to prevent infection. Using inbred lab mice, genetically matched to one another, seems to reduce the risk of parabiotic disease. Joined mice eat, drink and behave normally — and they can be separated successfully.# _' v" A% e, }+ P* e5 k+ f

' a* b. d9 |5 j# r7 B* J, R; ZIn McCay's first parabiotic ageing experiment, after old and young rats were joined for 9–18 months, the older animals' bones became similar in weight and density to the bones of their younger counterparts5. More than 15 years later, in 1972, two researchers at the University of California studied the lifespans of old–young rat pairs. Older partners lived for four to five months longer than controls, suggesting for the first time that circulation of young blood might affect longevity6.3 @" F' n! F8 j5 }% \4 a6 t

' r" n4 G: P6 U+ U: P5 W/ J6 }: p

Despite these intriguing findings, parabiosis fell out of use. Those who have studied the technique's history speculate that researchers thought they had learned all they could from it, or that the bar for getting institutional approval for parabiosis studies had become too high. Whatever the reason, the experiments stopped. That is, until a stem-cell biologist named Irving Weissman brought parabiosis back to life.8 h. e2 S" o# r# `1 l4 {0 s

# Q- |3 L, H8 s: j: j) x

' {5 x+ _+ f) n- q }, {8 w: NWeissman learned to join mice together at the age of 16, under the supervision of a hospital pathologist in the small town of Great Falls, Montana, in 1955. His supervisor was studying transplantation antigens, proteins on the surface of transplanted cells or tissues that determine whether they are accepted or rejected by the host. Weissman remembers adding a fluorescent tracer to the blood of one mouse in a pair and watching it go back and forth between the animals. “It was really amazing,” he says.4 R. s! @6 W# r' |8 E! n+ B

; t8 @ ~! z' C: j2 q: MHe went on to spend three decades studying stem cells and regeneration in natural parabionts, sea squirts of the species Botryllus schlosseri. In 1999, Wagers, then a new postdoctoral fellow in Weissman's Stanford lab, wanted to study the movement and fate of blood stem cells, so Weissman recommended that she use parabiotic mice and fluorescently label the cells she wanted to track in one animal of a pair. Wagers' experiments led to two rapid-fire discoveries on the nature and migration of blood stem cells7, 8. It also inspired her Stanford neighbours.3 m Z1 p. Y: M3 t7 g

7 Z+ G4 x. ]) m" Y; a

In 2002, Irina Conboy, a postdoctoral fellow in Rando's lab, presented one of Wagers' papers at a journal-club meeting. Michael Conboy, Irina's husband and a postdoc in the same lab, was dozing in the back of the meeting room.

# A* s0 }9 k% g2 C9 L4 I- M; t2 Q5 R' ~

The mention of stitching mice together jolted him awake. “We had been in discussion for years that ageing seems to be all cells in the body, that all tissues seem to go to hell in a handbasket together,” says Michael. Yet they had been unable to think of a realistic experiment with which to investigate what coordinates ageing throughout the body.# f0 {+ u8 ?- u" E

+ Z3 j' N1 @; C& N9 E

“I thought, 'Hey wait, they're sharing blood,'” says Michael. “'This could answer that question we've been asking for years.'” At the end of the presentation, he ran up to Irina and Rando. He had not even finished his pitch before Rando said: “Let's do it.”

G4 i4 o7 u* a: F4 X6 m; ~4 {9 E' c% v, G+ S* G3 {

“I thought, 'Hey wait, they're sharing blood. This could answer the question we've been asking for years.'”

# N6 |% [0 g5 D/ { xThe researchers teamed up with Wagers, who performed the old–young pairings for the experiment and taught Michael the technique (see 'Share and share alike'). Rando says that he did not expect the experiment to work, but it did. Within five weeks, the young blood restored muscle and liver cells in the older mice, notably by causing aged stem cells to start dividing again9. The team also found that young blood resulted in enhanced growth of brain cells in old mice, although the work was left out of their 2005 paper describing the results. All in all, the results suggested that blood contains the elusive factor or factors that coordinate ageing in different tissues.

1 c$ P$ X& I) A* m" m) m

+ @+ r# o/ h6 v. ?1 _1 V+ @6 X, iAfter the team published its results, Rando's phone started ringing incessantly. Some of the calls were from men's health magazines looking for ways to build muscle; others were from people fascinated by the prospect of forestalling death. They wanted to know whether young blood extended lifespan. But despite the hints that this was true from the 1970s, no one has yet properly tested the idea. It would be an expensive, labour-intensive experiment." _3 w5 }3 L# C- e# M W6 z+ s: e. g

0 a. ?; I9 c A0 Q1 e# U+ V

Instead, members of the original research team branched out into separate efforts to determine what exactly in the blood is responsible for the rejuvenating effects. In 2008, Irina and Michael Conboy, by then at the University of California, Berkeley, linked10 muscle rejuvenation to the activation of Notch signalling — which promotes cell division — or to the deactivation of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathway, which blocks cell division. Then, in 2014, they identified11 one of the age-defying factors circulating in the blood: oxytocin, a hormone best known for its involvement in childbirth and bonding, and already a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for inducing labour in pregnant women. Oxytocin levels decline with age in both men and women, and when injected systemically into older mice, the hormone quickly — within a couple of weeks — regenerates muscles by activating muscle stem cells., W7 x% w% R- n

. s7 y) ?5 @' a: U) m% r: ^All the organs

( E( O9 X+ R1 [) ` R' C$ qWagers was following up on the anti-ageing work at Harvard, where she had started her own lab in 2004. She recruited the help of experts in various organ systems to help her to evaluate the impact of young blood on their respective tissues. With neuroscientist Robin Franklin at the University of Cambridge, UK, her team showed12 that young blood promotes repair of damaged spinal cords in older mice. With Harvard neuroscientist Lee Rubin, she found13 that young blood sparks the formation of new neurons in the brain and olfactory system. And with cardiologist Richard Lee at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, she found14 that it reverses age-related thickening of the walls of the heart.

7 [( t8 M" _! X6 g6 J' |" W! o; z X6 S. F# C) J* u

With Lee, Wagers began screening for proteins that were particularly abundant in young blood but not old blood. One leapt out at them: growth differentiation factor 11, or GDF11. Wagers and Lee showed14 that direct infusions of GDF11 alone were sufficient to physically increase the strength and stamina of muscles, as well as to reverse DNA damage inside muscle stem cells. No mouse studies outside of Wagers lab have yet replicated the finding, but a similar protein in fruit flies extends lifespan and prevents muscular degeneration15.! @' C3 v- s |6 {) D7 }

( O, B1 Y' ~# s6 Z( t

“You often have these lucrative markets emerge on a slender foundation of credible work.”

' ~8 a) Q6 l4 Z& ~& wIt is perhaps fitting that parabiosis' newfound popularity has spread among labs with close ties. Wyss-Coray, who worked in the room next to Rando's lab, had previously discovered prominent changes in levels of proteins and growth factors in the blood of ageing humans and people with Alzheimer's disease. Following up on Rando's unpublished brain results, he used old–young mouse pairs to show16 that old mice exposed to young blood did indeed have increased neuron growth, and that young mice exposed to old blood had reduced growth. Plasma alone had the same effects. “We didn't have to exchange the whole blood,” says Wyss-Coray. “It acts like a drug.” Next, the team looked at overall changes in the brain, and found that young plasma activates brain plasticity and memory formation in older mice, and increases learning and memory. “We could not believe that this worked,” says Wyss-Coray.

) D/ z$ h4 X. }* N6 a8 D7 e0 U a0 M) `

Neither could the reviewers. The first time Wyss-Coray submitted the work to a journal, it was rejected, he says, responding that it was too good to be true. So his team spent a year repeating the experiments at the University of California, San Francisco — a different facility with different staff, instruments and tools. The researchers got the same results. “After that, I was really reassured,” says Wyss-Coray. “I'm convinced it works.”

* P0 @. N7 c7 l5 E0 l9 ?

P q9 b8 S5 K4 OHis research, published last May17, caught the attention of a company in Hong Kong owned by a family with a history of Alzheimer's disease, which is characterized by neuron loss. One family member's condition had reportedly temporarily improved after they received a plasma transfusion. So the company put forward the initial funding to translate Wyss-Coray's approach to human clinical trials. Wyss-Coray formed a start-up company, Alkahest in Menlo Park, California, and in September 2014 it began a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial at Stanford, testing the safety and efficacy of using young plasma to treat Alzheimer's disease. Six out of a planned 18 people with Alzheimer's, all aged 50 or above, have already begun to receive plasma harvested from men aged 30 or younger. In addition to monitoring disease symptoms, the researchers are looking for changes in brain scans and blood biomarkers of the disease.' R* p1 t: G& G9 f- \

{* A# [' d' m; h7 U( A

Bad blood?

! |4 d" d) ` e' wWagers is eager to see the results, but she worries that a failure would be difficult to interpret and so could set the whole field back. Plasma from a 30-year-old donor may not contain factors beneficial to patients with Alzheimer's, for example. She, Rando and others would prefer to see testing for a specific blood factor or combination of known factors synthesized in the lab, for which the mechanism of action is fully understood./ G8 r9 j4 {; {. r9 v/ p

0 g% W. Q9 H) F( RThere are also lingering concerns as to whether activating stem cells — which is what the young blood most often seems to do — over a long period of time would result in too much cell division. “My suspicion is that chronic treatments with anything — plasma, drugs — that rejuvenate cells in old animals is going to lead to an increase in cancer,” says Rando. “Even if we learn how to make cells young, it's something we'll want to do judiciously.”

b* g5 g! ^ k' ~5 r5 G* K% J. r: Y

Michael Conboy is concerned for another reason: he has seen enough paired mice die of parabiotic disease to be cautious about trying it in humans. “I would be leery” of any trial in which significant amounts of blood or plasma were transfused into an older person regularly, he says. Alkahest's chief executive, Karoly Nikolich, says that he understands the safety concerns, but he emphasizes that millions of blood and plasma transfusions have been carried out safely in humans. ?3 y$ [% a: M8 @" O$ L$ z

2 B e D, r0 d

The initial Alkahest study is expected to conclude by the end of this year, and the company plans to initiate further studies testing young plasma in the treatment of different types of dementia and age-related conditions.( [; ]+ l0 Y, o) u; n9 V& _

2 h6 J1 D9 [4 `& m) k

All the caution over young blood is justified, given the history of dashed hopes in the anti-ageing field. In the past two decades, researchers have identified the anti-ageing properties of numerous treatments, including calorie-restricted diets; resveratrol, a chemical found in the skin of grapes; telomerase, an enzyme that protects the integrity of chromosomes (see Books & Arts, page 436); rapamycin, an immune-suppressing drug that extends lifespan in mice; and stem cells, which decline in function and number as people age.

& Z$ J) h$ c" ?- ]" I- k6 s0 |, [4 `$ m9 J9 l1 P/ ?! r4 t

Only two of these — caloric restriction and rapamycin — have been shown to reliably slow or reverse the effects of ageing across many mammalian tissue types, but neither has turned into an anti-ageing treatment. The former has produced conflicting results in primates; the latter has toxic side effects.0 s( V3 S- ]0 F) ]

+ H! A2 p) |) q: F" @* W

Young blood, by contrast, seems to turn back the effects of ageing, potentially with few known safety concerns in humans and, so far, with corroborated results from parabiotic ageing studies in multiple labs. But scientists and ethicists still worry about the treatment being tried in people outside approved clinical trials before evidence on its safety and effectiveness is in. Unlicensed stem-cell transplants are already a booming industry, warns Mattson, and unlicensed transfusion of young blood would be even easier.

, v% ~# F: m' F( m9 L; ~9 ]

' U3 Z' _. |* L* ]/ j0 V, S“You often have these lucrative markets emerge on a slender foundation of credible work,” says Leigh Turner, a bioethicist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis who has studied the anti-ageing field.* D z* n; v$ @2 [) c

' S" O; o0 i; Q5 Z- A" ^# M; dFor now, any claims that young blood or plasma will extend lifespan are false: the data are just not there. An experiment to test such claims would take upwards of six years — first waiting for the mice to age, then for them to die naturally, then analysing the data. “If we had funding to do this, I'd do it. But we don't,” says Michael Conboy. Still, he adds, “I hope that someone, somewhere is.”

! L- x4 P, P$ z, s3 D( K2 J/ {

Nature 517, 426–429 (22 January 2015) doi:10.1038/517426a

6 @! e5 C2 \' } ^5 J7 [1 g* ^6 b2 l9 ?& `1 L3 S

http://www.nature.com/news/ageing-research-blood-to-blood-1.16762 |

-

总评分: 威望 + 2

包包 + 10

查看全部评分

|